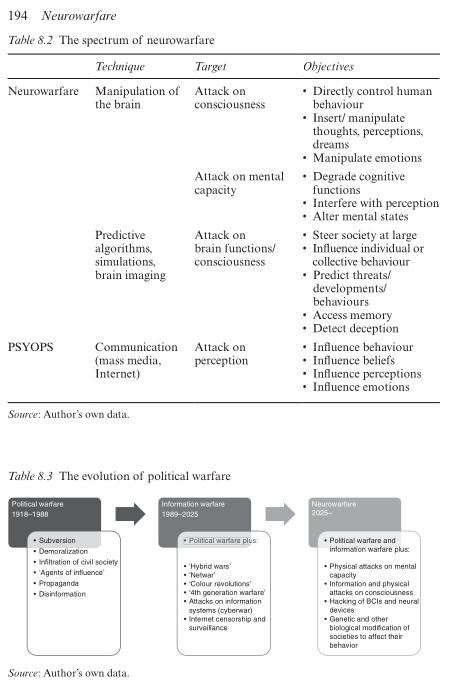

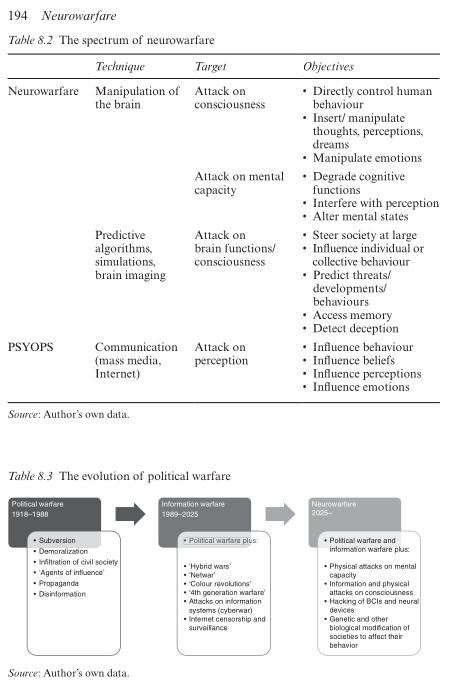

Armin Krishnan: Military Neuroscience and the Coming Age of Neurowarfare (Routledge, 2017, p. 194

”In our present technological environment, we are used to the idea that machines can be controlled from a distance by means of radio signals. The doors of a garage can be opened or closed by pushing a button in our car; the channels and volume of a television set can be adjusted by pressing the corresponding knobs of a small telecommand instrument without moving from a comfortable armchair; and even orbiting capsules can now be directed from tracking stations on earth. These accomplishments should familiarize us with the idea that we may also control the biological functions of living organisms from a distance. Cats, monkeys, or human beings can be induced to flex a limb, to reject food, or to feel emotional excitement under the influence of electrical impulses reaching the depths of their brains through radio waves purposefully sent by an investigator.

This reality has introduced a variety of scientific and philosophical questions, and to understand the significance, potentials, and limitations of brain control, it is convenient to review briefly the basis for normal behavioral activity and the methodology for its possible artificial modification, and then to consider some representative examples of electrical control of behavior in both animals and man.”

– José M. Delgado: Physical Control of the Mind : Toward a Psychocivilized Society (Harper & Row, 1969, p. 75) [pdf at archive.org]

“Unlike many intellectuals in the ’60s, who prophesied an Age of Aquarius in which man would reach his full potential, and in which humanistic values would triumph over the technocratic militarism of previous decades, Dick and Adorno agreed that even as technology was becoming more and more “user-friendly,” people were becoming not more, but less human all the time.”

"The greatest change growing across our world these days is probably the momentum of the living toward reification,” Dick writes a couple of years later [1975], in “Man, Android, and Machine.” How does this happen? In his earlier speech, Dick makes a Heideggerian argument that humans can actually be transformed into machines, by being “pounded down, manipulated, made into a means [rather than an end] without one’s knowledge or consent.” The “androidization” of humans, he warns, “has become a science of government and suchlike agencies now (…) until a time will perhaps come when a writer, for example, will not stop writing because someone unplugged his electric typewriter but because someone unplugged him.”

”Dick’s certainty that empathy and kindness can triumph over even the most insidious entertainment-enforced normality is also the theme of Flow My Tears, which explores the “subtle, intricate relationships which exist between the sexes” — in this case, between General Felix Buckman and his bisexual leather-queen twin-sister/wife — and which ends with Buckman crying over her death, and being embraced by a total stranger. In a 1970 letter to a friend about Flow My Tears, Dick writes, “In answer to the question, ‘what is real?’ the answer is: this kind of overpowering love.” For Dick, in a world where we’re all becoming androidized, acts of unselfish kindness are the only remaining proof of one’s humanity.”

– Joshua Glenn: Philip K. Dick (Hermenaut #15, 1999 / hilobrow.com)

Armin Krishnan: Military Neuroscience and the Coming Age of Neurowarfare (Routledge, 2017, p. 194

mosh @ terran hacker corps: A Singular Rapture (Green Anarchy #20, Summer 2005)

Ran Prieur: Don't Fear the Singularity (Green Anarchy #22, Spring 2006)